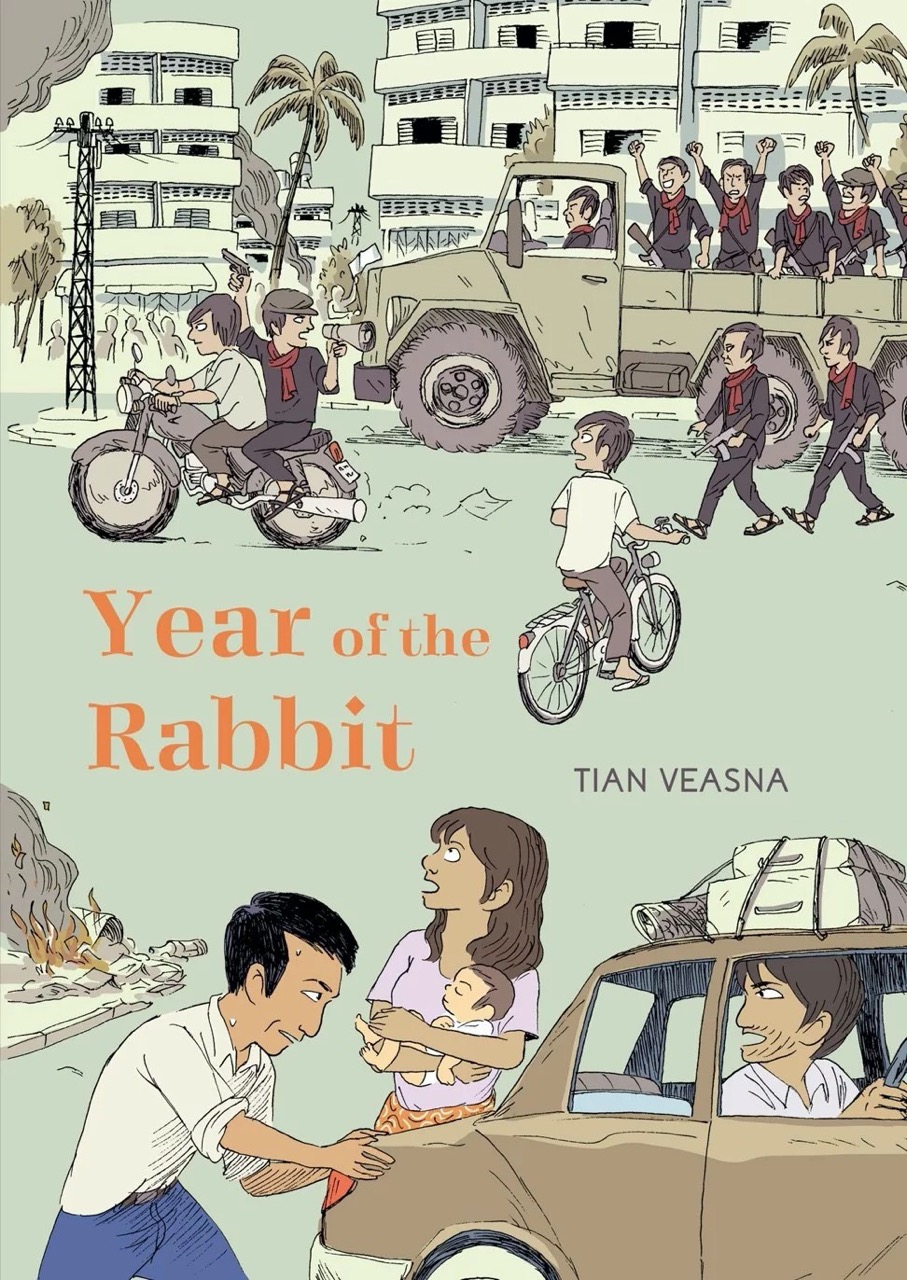

Horrors of Khmer Rouge Captured in Powerful Graphic Novel That’s Gripping But Never Gruesome

The Khmer Rouge takeover of Phnom Penh is seen in a new light in Year of the Rabbit, a graphic memoir that follows the journey of Lina, Khim, their son Chan, and their extended family members. Graphic in format, graphic in content, it is a story of resilience and hope, and a profound testimony to one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century.

On April 17, 1975, young soldiers victoriously enter the Cambodian capital. Dressed in black, red krama around their necks, brandishing AK-47 rifles and accompanied by tanks, they have come to build a new society, free from capitalists and foreign influence. The day, coinciding with the traditional Khmer New Year that marked the start of the Year of the Rabbit, marks the beginning of Year Zero.

Three days after the fall of Phnom Penh, Lina gives birth to baby Chan, the author. The story of his birth sets the tone of the graphic novel. “Chan is the type of tree outside the hut, and Veasna means destiny, in the hope that he’ll have a happy life,” she says.

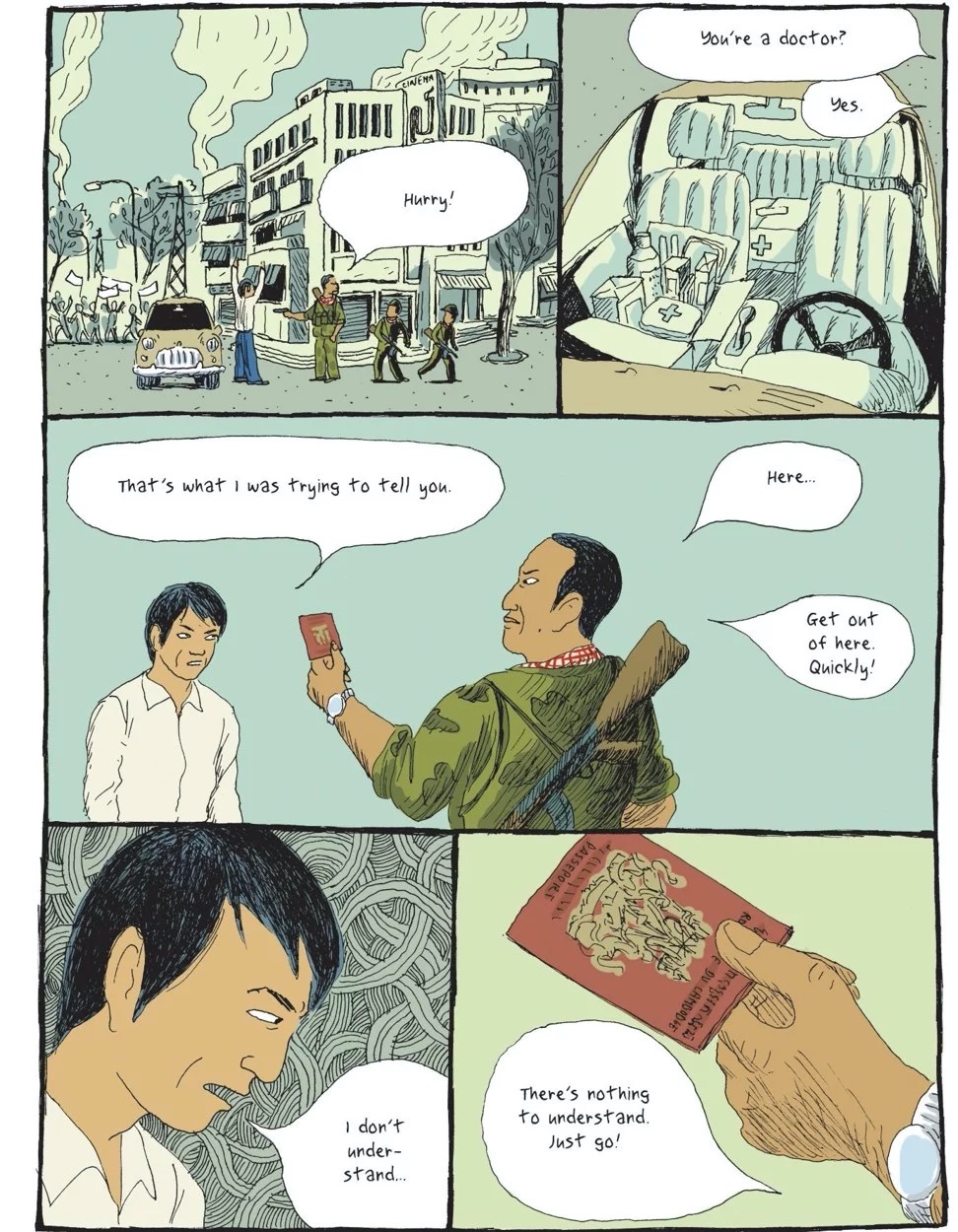

In this page of Year of the Rabbit, Tian Veasna’s family are told that the Khmer Rouge are evacuating Phnom Penh.

Lina and her husband, Khim, are helped by a midwife in the middle of the night, in a makeshift shack in Ta Prom village, their first stop after leaving their home in Phnom Penh.

They followed Khmer Rouge instructions to go back to their home village as imminent US bombings were feared, one of many lies told by Angkar (Khmer for “the organisation”). “Don’t worry. We’ll be back in three days,” a relative consoles another, as a farewell is bade to a beloved scooter.

The family will separate and reunite several times during their attempt to reach Battambang, survive the unbearable conditions of forced labour in the rural areas, and make a desperate effort to cross into Thailand when a window of opportunity presents itself.

The cover of Year of the Rabbit by Tian Veasna.

As “new villagers”, urban dwellers uprooted from Phnom Penh as opposed to the peasants established over generations, they are spared nothing in the village they end up in and in their work units.

Khim is a doctor and Lina’s father, Kongcha, was a businessman. After a brief period of innocence, they soon understand the urgency of disguising their former identities to survive.

Centred on family, the persistence of traditional kinship-based relations permeates the story, unbending in the face of the expected new society proclaimed by Angkar, the only family of Democratic Kampuchea.

It highlights the strength and resistance of the old ways: a mother who can’t let go of her child, a widow who honours her late husband through forbidden religious ceremonies.

Different family members cross paths with friends, family, and acquaintances, often in the most uncanny of circumstances.

Before the arrival of the Khmer Rouge in Phnom Penh, Tian Veasna’s father, Khim, worked as a doctor.

It recalls a pre-Khmer Rouge society built around bonds and the reciprocal exchange of favours, conveys a sense of smallness despite the vast Cambodian countryside, and attests to the reality that every Cambodian knows of victims in their immediate social and family circle.

The family will also receive help through surprising encounters, a reminder of the drop of humanity which remains despite the prevailing nightmare.

This is, of course, far from the first Khmer Rouge-era memoir; one of the best-known is Loung Ung’s First They Killed my Father, later turned into a film by American Angelina Jolie.

In Year of the Rabbit, unlike this earlier work, Tian Veasna is not only graphic artist and illustrator but omniscient narrator, with a point of view which lends itself to discovering the dilemmas and experiences of family members. The graphic novel format is a judicious choice, as it makes accessible a topic that might otherwise be seen as intimidating.

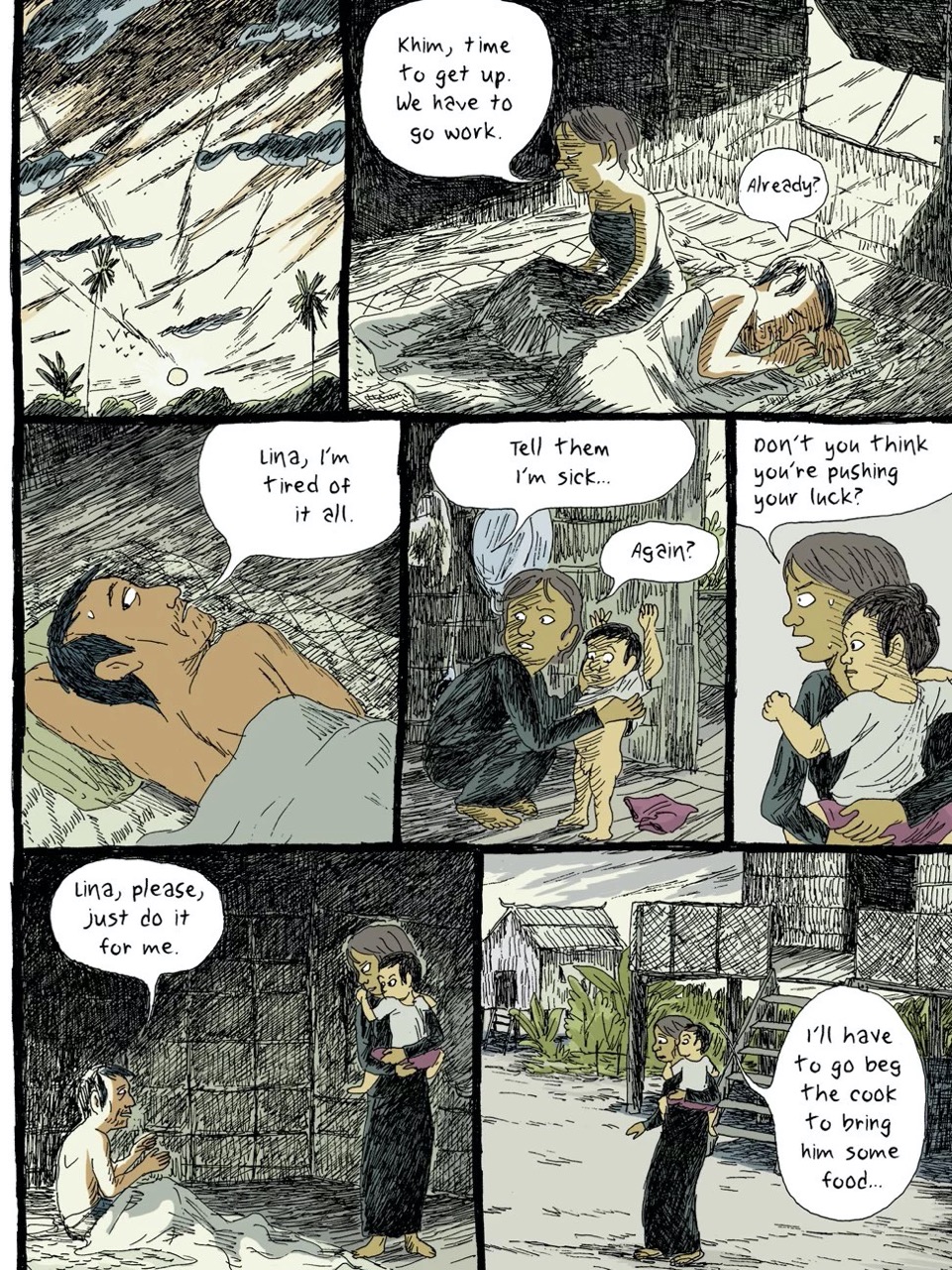

A page from graphic novel Year of the Rabbit.

The book’s muted colour palette evokes the faded walls of colonial mansions still to be found in Phnom Penh. The detailed drawings convey drama, fear, hopelessness, and love. Crows make a regular appearance, ominous animals that are witness to the unfolding genocide. Hunger is ever present, faithful to survivors’ accounts.

A quarter of the Cambodian population is estimated to have died between 1975 and 1979. Tian Veasna recalls that 150 new mass graves are still being found every year.

Rithy Panh, who penned the preface to the book and who has dedicated much of his life to the memorialisation of the Khmer Rouge genocide, writes of “an impossible mourning”. How could mere words, situations, and characters express the unthinkable, without falling in the trap of caricature? Tian Veasna pulls it off brilliantly.

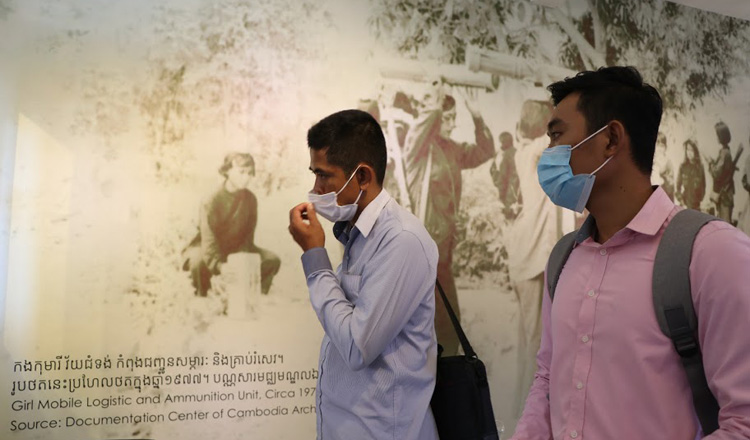

Cambodians leave Phnom Penh after Khmer Rouge forces seized and emptied the Cambodian capital in April, 1975. Photo: AFP

His book is gripping but never gruesome, and becomes a page-turner as one develops profound empathy for the family. First released in French, this recent translation, published by Drawn & Quarterly, offers English readers an accessible way into the tragedy of modern Cambodia by an author who survived it.

Source: SCMP