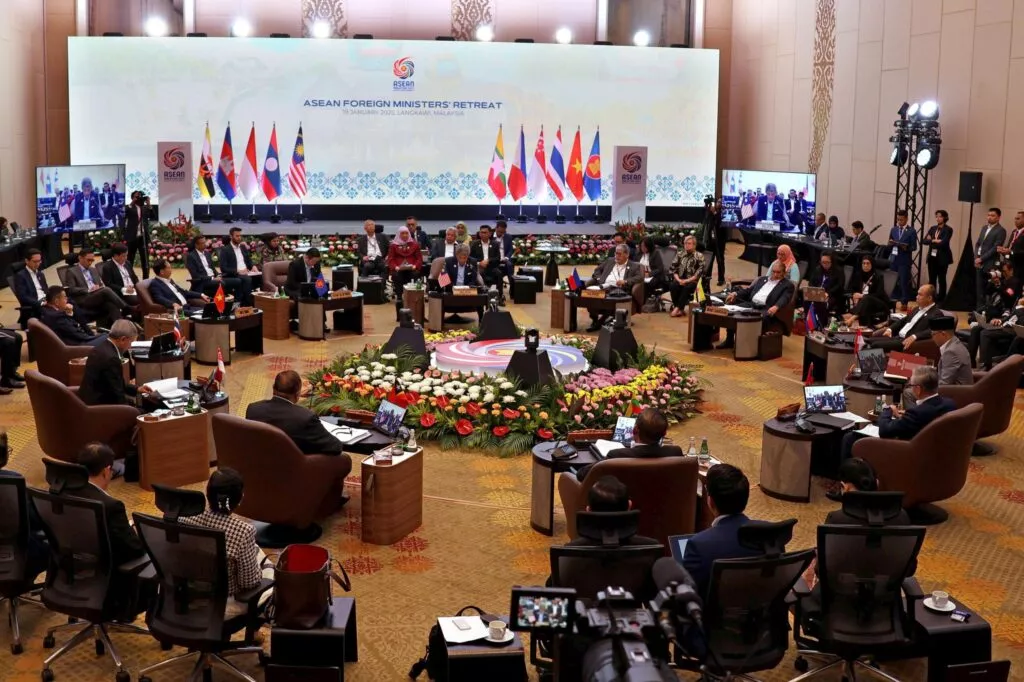

ASEAN adapts and advances as global politics shift

ASEAN, now under Malaysian leadership, is well-equipped to manage international challenges in 2025 due to its vibrant economy, strategic political toolkit and extensive foreign investment, including from countries such as the United States, Japan, South Korea and China. Though facing risks that may affect its economic advantages, including potential tariffs imposed by the United States that may harm China–ASEAN trade, ASEAN’s practice of multifaceted engagement, historical experiences and its emphasis on inclusive relations will aid the region in navigating an increasingly complex global landscape.

ASEAN is better equipped than many in the international community to handle the challenges of 2025. Expanding competition between the United States and China, the slowing Chinese economy and the new US leader’s unpredictability will trouble Southeast Asian countries — and many others.

But ASEAN, now under experienced Malaysian leadership, enters 2025 with a relatively vibrant economy. ASEAN’s GDP is about the same as India’s, it has healthy growth rate predictions, strong foreign investment and is China’s largest trade partner. In political matters, ASEAN has moved more slowly, but it possesses a strategic toolkit that can help the organisation to assert agency in a more fluid regional order.

Throughout 2024, Southeast Asia drew investment from many quarters, helped by the contest between the United States and China. US technology companies are investing in the region, including setting up elaborate energy-consuming data centres. Japanese, South Korean, European and Chinese manufacturers are also relocating to Southeast Asia to avoid crushing US tariffs.

ASEAN countries have avoided being locked into one side or another in the contest of major powers. For instance, Indonesia joined BRICS in January 2025 but also declared a determination to enter the Western-led Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Though some see Southeast Asia as the biggest winner in global trade over the next decade, the dangers are obvious. The United States may impose tariffs not just on China but also on countries like Vietnam where trade is unbalanced and import-heavy. If this happens, ASEAN’s investment advantages would be reduced, even where workforces are being upskilled to handle semiconductor and other higher-value manufacturing. Another risk is that US actions will damage China–ASEAN trade, for instance by driving China to dump products on Southeast Asia, undermining local manufacturing.

In security matters, Southeast Asian countries again engage in every direction. Singapore’s military has been cooperating with China and in mid-2024 six ASEAN countries took part in maritime exercises with the United States. Under its present leadership, the Philippines has been more combative towards China, bolstered by closer alignment with the United States — though it also engages in the ‘China–Philippines Bilateral Consultation Mechanism on the South China Sea’.

Meanwhile, China has been helping Cambodia with naval training and is involved in developing the Ream Naval Base. The United States supported this initiative in the past, but cut funding in 2018. Despite China’s strong role today, Cambodia insists it is the owner, not China — and that the base is open to all friendly navies.

Whether Southeast Asian states can maintain their strategic autonomy if the US–China contest sharpens even further remains to be seen. US President Donald Trump has already displayed antagonism toward BRICS and Southeast Asia may also face a more muscular minilateralism — which was hinted at in the renewed stress on security concerns at the 2024 Quad Foreign Ministers’ Meeting. But in handling this increasingly turbulent region, ASEAN brings economic vitality and a valuable — and historically grounded — set of approaches to foreign relations.

Southeast Asian countries have been portrayed as quintessentially pragmatic, advancing their own interests — especially economic interests — and hedging between major powers. But ASEAN’s strategic heritage has more substance than this. For example, Malaysia insists its foreign policy is both principled and pragmatic.

ASEAN’s stress on regional community building and on unity being essential to Southeast Asia’s security means the organisation, again under Malaysian leadership, will act with meticulous care regarding South China Sea contests or Myanmar. There is a contrast to be negotiated in 2025 between Philippines’ combativeness and Indonesia’s declared support for practical cooperation with China in disputed maritime areas.

Another element in ASEAN’s heritage is an insistence on inclusivity. Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s moves toward China and Russia, while affirming his friendship with EU countries and the United States, should be viewed in this light — not as mere hedging. The willingness to be open to all sides, despite differences in governing ideology, has been emphasised time and again across Southeast Asia. ASEAN leaders will not be bothered when Trump’s United States speaks less about the liberal rules-based order and puts more stress on transactional engagement.

ASEAN gives institutional expression to inclusivity with bodies such as the East Asia Summit, the ASEAN Regional Forum and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, with their wide membership and patient dialogue. Like-minded minilaterals such as the Quad may move more quickly in practical areas — but they tend to be adversarial and liable to exacerbate regional divisions.

Though alliance-forging is a typical response to a rising power in certain parts of the world, Southeast Asian regimes seem relatively comfortable working with hierarchies and their success in asserting agency is caught in the Southeast Asian folk image of the little mouse deer. Small but shrewd, the mouse deer is portrayed as outmanoeuvring the larger animals in the forest.

In the emerging Indo-Pacific, with less stress on alliances and ideological commitments, ASEAN countries possess valuable historical experience. Flexibility in political and economic engagement — and a record in building inclusive relations and institutions — may prepare them to negotiate, and even assist in shaping, a post-liberal Indo-Pacific order.

Anthony Milner is Professorial Fellow at the University of Melbourne, Visiting Professor at the University of Malaya and Emeritus Professor at The Australian National University.

Source: Eastasisforum