Indonesia’s economic diplomacy must begin at home

Indonesia’s efforts to expand its export reach through economic diplomacy are at odds with low productivity and protectionist policies that foster an unfavourable domestic business environment. The country’s imperative is to improve regulatory efficiency, alleviate protectionist measures, streamline bureaucracy and create a predictable business environment to fully capitalise on international market opportunities and maintain competitiveness amid global trade wars.

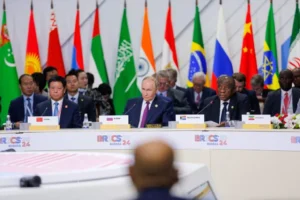

Started as Joko Widodo’s initiative, economic diplomacy has continued to be Indonesia’s foreign policy priority under President Prabowo Subianto’s leadership. The chief objective is to expand Indonesia’s export reach by securing greater access to international markets. But low productivity and an unfavourable business environment at home will keep hindering Indonesia’s ability to compete in international markets.

To substantiate economic diplomacy, Indonesia must first improve regulatory efficiency and alleviate protectionist policies that have long undermined its attractiveness as an economic partner. Failing to fully leverage its economic network leaves Indonesia vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, especially if US President Donald Trump escalates his trade war to a global scale.

Trump’s March 2025 decision to double the tariff on Chinese imports to 20 per cent, up from the initial 10 per cent imposed in February, threatens to disrupt Indonesia’s exports, particularly electronics and machinery that depend on Chinese inputs for production. These tariffs could escalate further as Trump has pledged to impose a 60 per cent tariff on China and a 10–20 per cent tariff on all imports.

Indonesia has long recognised the importance of expanding and diversifying its economic network to mitigate supply chain disruptions. Amid the trade war during Trump’s first term, economic diplomacy tripled the number of Indonesia’s trade agreements, increasing from just nine in 2003–13 to 27 in 2014–24.

Despite the proliferation of trade agreements, Indonesia’s trade network remains underdeveloped, with slow growth and limited impact. While Indonesia’s manufacturing exports increased from US$127.02 billion in 2019 to US$186.59 billion in 2023, the trade sector’s contribution to GDP has stagnated at around 40 per cent over the past decade. This is the lowest in Southeast Asia, especially compared to Vietnam (166 per cent) and Thailand (129 per cent) in 2023.

Ultimately, the success of economic diplomacy abroad depends on domestic capacity. Indonesia’s economic diplomacy has focused on opening new international markets without strengthening its export capacity. Without a strong industrial base, Indonesia cannot fully capitalise on the market opportunities created by free trade agreements.

To revitalise economic diplomacy, government reform must begin by improving bureaucratic efficiency and alleviating business regulations that deter investment needed to boost Indonesia’s export industries.

Foreign businesses have long complained about the inconsistency of regulation in Indonesia. The government has attempted to address this by implementing the Omnibus Law on Job Creation, which aims to streamline regulations of business. But this policy is undermined by protectionist measures that restrict the flow of goods and investment, including tariffs, export restrictions and local content requirement policies.

Estimates from Global Trade Alert suggest that Indonesia has implemented the highest number of protectionist measures in Southeast Asia, with 474 measures enacted between 2018–24. In contrast, Vietnam and Thailand — preferred investment destinations for major companies such as Nvidia — only implemented 107 and 175 measures, respectively.

While protectionist policies might be necessary to develop infant industries, the impacts of protectionism are detrimental to capital-intensive sectors that are highly dependent on foreign investment. A study by Yessi Vadila and David Christian shows that products subject to local content requirements in general experienced a decline in export volume and value over five years of implementation from 2004–20. Local content requirements in the high-tech sector will not increase competitiveness unless Indonesia first secures the investment needed to develop technological capacity in the sector.

The policy has deterred foreign investment and reduced Indonesia’s export competitiveness due to the added cost of using more expensive local components for production. Riandy Laksono’s calculation shows that Indonesia’s revealed comparative advantage — a score measuring competitiveness of products in global market — of high demand products from 2017–21 was consistently below one, indicating Indonesia’s low export competitiveness despite implementation of local content requirements.

Alleviating protectionist policies such as local content requirements would create more incentives for investment. These investments will not only boost Indonesia’s export productivity but also diversify its economic partnerships.

Reform should also create bureaucratic certainty. Reducing overlapping and conflicting regulations would create a favourable business environment. A Japan Bank for International Cooperation survey of Japanese companies, for example, found that ‘stable political and legal practices’ are a top consideration for firms moving manufacturing operations to other countries.

Indonesia’s government efficiency could become a major challenge, as Prabowo’s administration has expanded the number of ministerial posts from 34 to 48 to accommodate his broad ruling coalition, which includes almost all political parties represented in the parliament. With existing bureaucratic fragmentation, this government expansion could further complicate inter-agency coordination.

Prabowo’s latest decision to massively cut public services spending — instead of simplifying government structure — risks creating government inefficiency that businesses will struggle to navigate. Vietnam’s step to streamline bureaucracy by reducing the number of ministerial-level agencies from 30 to 22 offers an example that Indonesia could follow. Only under an efficient and adaptive political system can an economy prosper.

Maintaining extensive economic partnerships is crucial, but without robust domestic policies, the networks Indonesia has built through economic diplomacy will remain an empty husk. To translate market access into tangible trade and investment gains, Indonesia must address regulatory inefficiencies, alleviate protectionist measures and create a more predictable business environment. Without decisive reforms, Indonesia will struggle to stay competitive.