Indonesia’s BRICS accession underscored by Prabowo’s self interest

Indonesia’s decision to join BRICS under the leadership of Prabowo ostensibly stems from an ambition to position the nation as an advocate for developing countries and to reduce geoeconomic global tensions. But the move is seen as largely symbolic with minimal tangible benefits. Existing voices within BRICS have already laid claim to leadership over the Global South. And despite potential economic gains, China’s economic dominance within BRICS raises questions about the actual economic benefits of joining the coalition. By overlooking ASEAN in pursuing global leadership, Prabowo’s ambitions are seemingly driven more by self interest rather than strategic considerations.

In his 2025 Annual Press Statement, Indonesian Foreign Minister Sugiono provided justifications for President Prabowo Subianto’s decision for Indonesia to formally join BRICS. He touted Indonesia’s fast acceptance into BRICS as a personal accomplishment of Prabowo and described Indonesia’s positioning in the grouping as an advocate for the interests of developing countries.

Sugiono also described Indonesia’s decision to join BRICS as a manifestation of its ‘independent and active’ (bebas aktif) foreign policy. Indonesia is also active in other multilateral groupings, including its ongoing process to join the OECD.

In other words, Indonesia’s entry into BRICS is a manifestation of Prabowo’s ambition to be the leader of the Global South, who will actively bridge between the Global ‘North’ and ‘South’. Prabowo believes that Indonesia had the capability and willingness to do so — and that he is the right person to take the lead.

There are undoubtedly some potential benefits in joining BRICS for Indonesia. BRICS is seen as a credible alternative to other major Western-centric groupings, making it attractive to countries in the Global South tired of Western dominance. It could also expand Indonesia’s potential export markets, considering that BRICS states account for 46 per cent of global GDP and over half of the world’s population, if Indonesia gains access to preferential trade treatment with BRICS members.

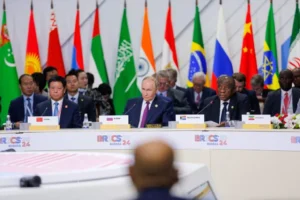

The problem is that at this point, the benefits of joining BRICS are mostly symbolic. First, it will be difficult for Prabowo to become the leader of the Global South when many loud voices already exist within BRICS. South African President Cyril Rhamaposa, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi have all already staked their claims to this role.

Prabowo is essentially stepping into an already rapacious bunch, making it difficult to be heard above the din. A parallel can be drawn with the 1961 Non-Aligned Movement Summit in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia, where then-Indonesian president Sukarno and then-Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who both regarded themselves as the leaders of the Third World, clashed over their vision of the Third World Movement ‘to a point necessitating friendly intervention by third parties on the very first day of the conference’.

And with China dominating BRICS through the sheer force of its economy and Russia trying to steer the grouping to challenge US global leadership, it is difficult to see how Prabowo can effectively use BRICS to lead the Global South while maintaining Indonesia’s independent and active foreign policy.

Second, regardless of economic potentials from joining BRICS, China — a key member of BRICS — has already been Indonesia’s biggest trading partner. And most trade between BRICS members comes from trade with China, while trade between other members remains low. The exception is trade between India and Russia, which skyrocketed in the aftermath of Western sanctions after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Adding the economic problems currently facing BRICS states to the calculus, the economic gains Indonesia can expect from joining BRICS remains questionable.

Third, the United States under President Donald Trump seems less willing to play the usual diplomatic niceties. This is clearly shown by the new administration’s shoot-from-the-hip approach, including in its imposition of tariffs on its closest neighbours and partners in what has been called ‘the dumbest trade war in history’. Considering the ongoing tariff war between the United States and Indonesia’s ‘sleepwalking’ into strategic alignment with China in pursuit of economic gains, Indonesia’s entry into BRICS may cause more problems than it is worth.

And more troubling is how Prabowo, in his desire to accrue foreign policy accomplishments, is seeming to neglect ASEAN. In December 2024, Indonesian Foreign Minister Sugiono skipped an informal ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Bangkok to accompany Prabowo to Cairo to attend the Developing Eight (D–8) Summit. In his Annual Press Statement, Sugiono barely mentioned ASEAN and did not articulate any new agendas, commitments or policies about Indonesia’s leadership in ASEAN.

In his haste to portray himself as a global leader, Prabowo seems to be abdicating from Indonesia’s regional leadership. This could prove unwise — ASEAN is arguably the most effective platform that Prabowo can use to advance Indonesia’s ambitions to become the leader of the Global South.

While Prabowo may see many benefits in joining BRICS, he seems to be motivated more by personal ambition for international recognition and to be able to declare achievements his first 100 days as president, rather than clear strategic considerations around strengthening Indonesia’s position as the leader of the Global South.

Yohanes Sulaiman is Lecturer in the School of Government at Jenderal Achmad Yani University, Bandung, Indonesia and Nonresident Fellow at The National Bureau of Asia Research.