Rise and Fall of Cambodian Refugee ‘Donut King’ Charted in Award-Winning Film

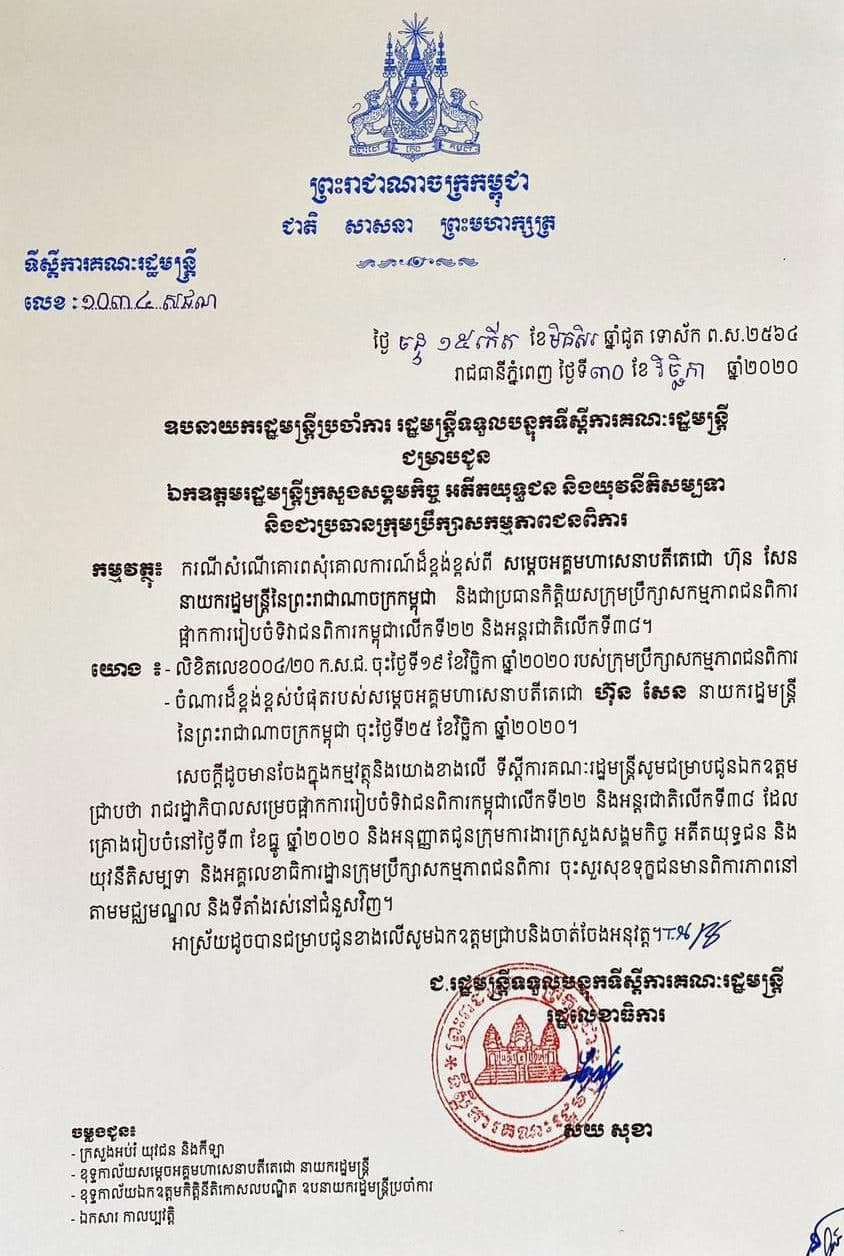

Ted Ngoy once owned a huge chain of doughnut shops across the US state of California and was known as “The Donut King”. Photo: Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Ted Ngoy once owned a huge chain of doughnut shops across the US state of California and was known as “The Donut King”. Photo: Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Filmmaker Alice Gu is a self-professed foodie – but she found herself genuinely stumped when her son’s nanny told her about a particular confection two years ago.

“I had never heard of these ‘Cambodian doughnuts’ … and when I tried them it was an out-of-body experience.” It was delicious, she says, even though “it was just a glazed doughnut”.

When Gu searched for the snack online, she came across a Cambodian refugee named Ted Bun Tek Ngoy who had once owned a huge chain of doughnut shops across the US state of California. She then “literally devoured everything” about Ngoy, aka “The Donut King”.

“Someone had to make a movie about him, and that someone had to be me,” the 42-year-old, second-generation Taiwanese-American says by phone from Los Angeles, where she was born and raised.

Her documentary, The Donut King, was expected to premiere at the SXSW Film Festival in Austin, Texas, in mid-March, but the event was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic. Nevertheless, the film was awarded Special Jury Recognition for Achievement in Documentary Storytelling.

In 94 minutes, Gu tells the rags-to-riches-to-rags story of Ngoy’s doughnut empire, and how he lost it all gambling.

Tracking down Ngoy wasn’t difficult – Gu simply called DK Donuts in Santa Monica, one of the most popular doughnut shops in California, and discovered that the young woman on the other end of the line was his great-niece.

Ngoy, now 78 years old and living in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh, had returned – bankrupt – to the country in the 1990s. Although he is keeping busy and making money with new projects, he set aside time to talk to Gu so she could properly tell his story.

Ngoy was born in Sisophon, a Cambodian town near the Thai border. His father left when he was five years old, and his mother – from Shantou in China’s Guangdong province – did not speak the Khmer language, which meant they struggled to get by. Every day, for 15 years, she traded goods on the border.

It was from his mother that Ngoy learned the importance of working hard, kindness and a good education. He admits that, perhaps because he was poor, he often felt like he had nothing to lose and was willing to take risks.

This was especially true when it came to love. In the evenings, Ngoy would play the flute for Suganthini Khoeun, a girl in his class and the daughter of a high-ranking official, near her home, and they would send messages back and forth via her maid. Eventually, despite her family’s disapproval, the couple married.

Through his brother-in-law, Ngoy went on to become a major in the Cambodian army, where he was responsible for payroll and training soldiers. Eventually, though, the rise of revolutionary politician Pol Pot and the communist Khmer Rouge in the country prompted Ngoy to flee with his wife, three young children, two cousins and a nephew to the United States in 1975.

One of Ngoy’s first jobs in the US was as a service station attendant. One night, he smelled something sweet in the air and, after following his nose, arrived at a busy doughnut shop. When he tried one, he was immediately reminded of num kong: deep-fried Khmer doughnuts made with coconut milk.

In an interview with the Post, Ngoy recalls a conversation he had with the woman manning the counter.

“‘Lady, if I save US$3,000 can I open a shop like this?’ – and she gave me advice: ‘You are crazy. You will throw away your savings. Why don’t you go to [chain restaurant] Winchell’s Donut House? If they accept you, they will train you for three months as a management trainee, and they will give you a shop so you don’t use your savings.’”

As soon as his shift was over at 6am, he asked a friend to take him to the Winchell’s headquarters. The company had never hired an Asian person before, but Ngoy’s persuasiveness and eagerness won over the general manager.

“He said, ‘Ted are you ready?’ In fact, I did not have any sleep yet. I said, ‘Yes I’m ready!’ … And he put me to work immediately to clean the bathrooms. But because I wanted to make it, I conquered my tiredness and worked another eight hours,” Ngoy says.

After three months of training as a baker and manager, Ngoy was given a shop to run. After a year, when he had saved enough money, he bought his own doughnut shop and named it Christy’s – a name that his wife later adopted.

To save as much money as possible, Ngoy enlisted the help of his two oldest children, who were eight and nine years old at the time. He woke at 2am to make doughnuts, and two hours later would wake his children so that they could fold cardboard boxes.

In the film, the unhappy memories of being dragged out of bed so early in the morning are clearly still vivid for Chet and Savy. As adults, though, they understand their parents had been working hard to create a better future for them.

By 1979, Ngoy had 25 doughnut shops around California. At the time, there were many Cambodian refugees arriving in the US and he sponsored more than 100 families who claimed to be related to him. “Everyone looked to me because I’m the wealthiest, I’m successful in running [a] doughnut business … I can give them a job or I can lease a store for them, or train them to do the doughnut trade, so I cannot say no.”

When you gamble, you do not have the intention of ruining the business … I lost my mind. I was not the same person as before anymore. So I hated myself

Ted Ngoy

At his peak, Ngoy owned 65 shops and his wealth was estimated at US$20 million. His family had moved from a condominium to a three-storey, US$1 million mansion. After several years of hard work, the family took their first holiday and they went to Las Vegas.

A few return visits later, however, Ngoy began gambling. By the late 1980s, Ngoy had frittered away so much of his fortune that he’d had to sell his shops to his Cambodian “relatives”.

A decade later, he had lost his mansion and was living back in Cambodia. Christy had divorced him, and his relationship with his children had broken down. Still, he was unable to kick his gambling addiction.

Ngoy joined Gamblers Anonymous, and briefly became a monk at a Buddhist temple in Washington, but found himself back at the casino a few months later.

“When you gamble, you do not have the intention of ruining the business; [gamblers] try to get money and then run to Las Vegas. I lost my mind. I was not the same person as before anymore. So I hated myself,” Ngoy says.

“I feel sorry for my children, for Christy. I wanted to stop but there are two types of gamblers: one really doesn’t want to quit, because they have so much fun gambling. And then there’s me: I wanted to stop but I didn’t know how.”

In making The Donut King, Gu felt it was important for Ngoy to return to California to see his family and the refugees he helped all those years ago. “He hadn’t quite owned up to all the bridges he had burned. He asked, ‘Do I have to?’ He was afraid he would be lonely,” Gu says.

She took Ngoy back to his first condo, then his mansion, and several of his old doughnut shops, visiting owners who he had once pressed for loans to feed his addiction.

“I had a sad feeling [because] it reminded me of the glorious days of being so wealthy and suddenly I became old … I felt sorry for committing stupid mistakes. I cannot change the past. I felt remorse,” he says.

Ngoy was able to make amends with those he had known before, with the documentary following him visiting each shop – and eating their doughnuts.

“People are human; they know what’s wrong, what’s right. If I intentionally cheated people, I don’t think they would forgive me. But because of [what] the devil gambling did to my life, people understood and they all forgave me,” he says.

Two years ago, Ngoy published a memoir, also called The Donut King, in English and Khmer. He is having it translated into Thai and, maybe later, into Chinese.

“I want to let the younger generation know about my legacy: a refugee from nowhere, who went to a powerful country and changed the doughnut market from American mainstream doughnuts to Cambodian. That’s history.”

South China Morning Post