Across Languages And Generations, One Family Is Reviving Cambodian Original Music

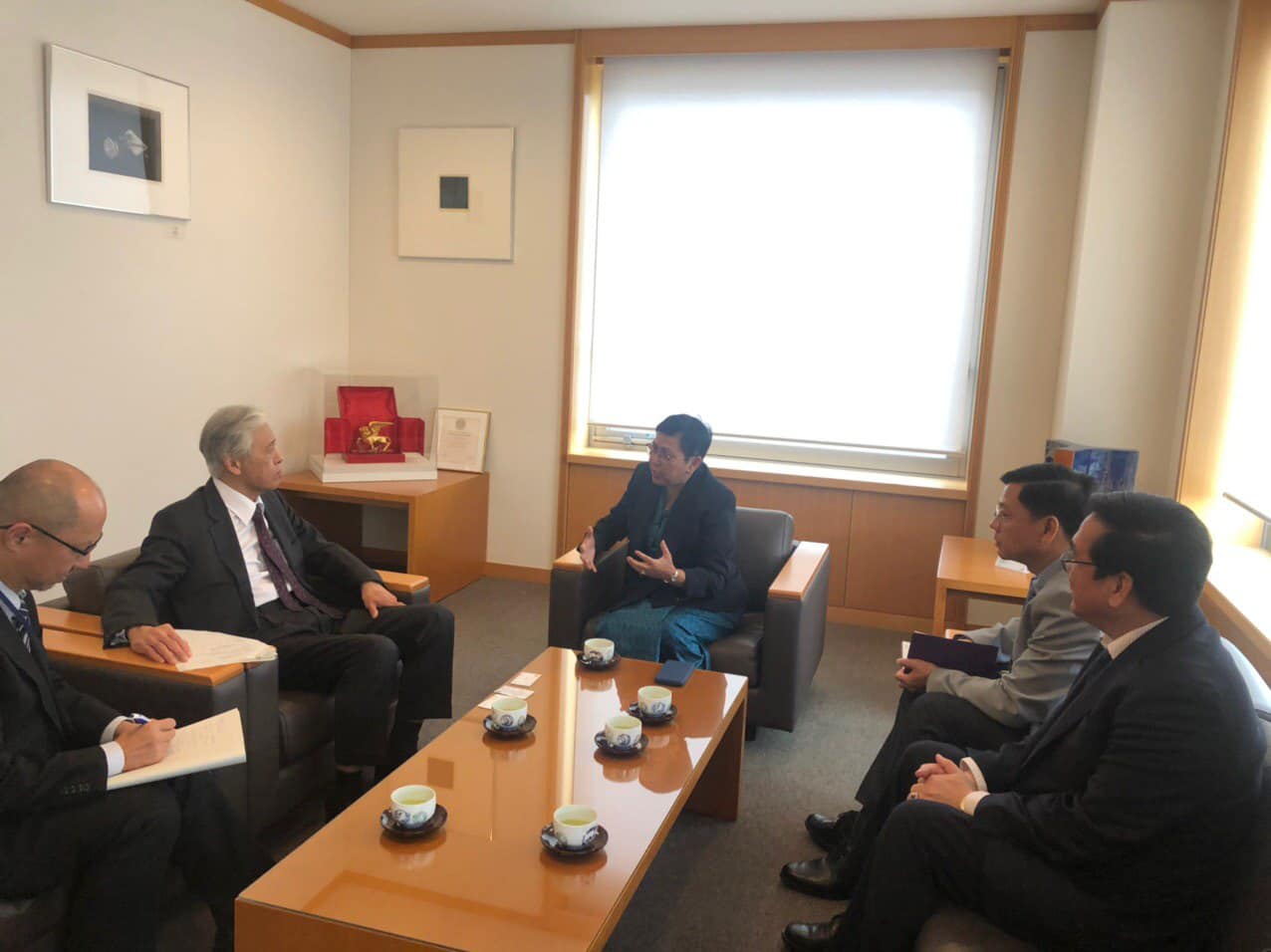

For fans of original music in Cambodia, the movement is about more than just the songwriters. "People see original music as this living proof that we are moving forward," Laura Mam says.

Courtesy of the artist

For fans of original music in Cambodia, the movement is about more than just the songwriters. "People see original music as this living proof that we are moving forward," Laura Mam says.

Courtesy of the artist

Laura Mam is one of Cambodia’s biggest pop stars, but she wasn’t born or raised in the country. She’s American, and even though both of her parents are originally from Cambodia, she hardly spoke a word of the country’s language, Khmer, when she first became famous there.

Laura’s fame happened almost by accident. It all started 10 years ago, at her mother’s house in San Jose, Calif. It was Christmas Eve and Laura was home after graduating with a degree in Anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley.

“I had been writing music and my mom was kind of interested in what I was doing. I think I went to her room and I was playing this song. I was like ‘Hey mom, could you write lyrics in Khmer on top of it?’ ” Laura says.

There was only one problem: Laura’s mother, Thida, had never written lyrics before.

“The first song, I didn’t understand what I was doing and I didn’t know how to rhyme,” Thida says.

But Thida gave it a try, and it turned out she had a knack for it. They called the song “Pka proheam rik popreay” which means “morning flower is beautifully blossoming.” A few months later, Laura and some friends made a music video and uploaded the song to YouTube, not expecting much.

The morning after the music video went live, they woke up to a big surprise. The video had reached 75,000 views in the course of a single night. But it wasn’t just about the numbers. The viewers’ reactions stunned them.

“The comments were all just like ‘Yes! Original Cambodian music, oh my god!’ ” Laura remembers. The comments came streaming in from all over the world.

“Not just the Cambodians in Cambodia, it was also diaspora in France, Australia and Canada,” says Thida.

But why were people all over the world this excited about one song in Khmer from a mother and daughter in California? To understand that, we have to cross an ocean and go back in time, to the Cambodia of Thida’s childhood.

“I was from Phnom Penh. And when I was growing up the music scene was huge. During that time there were all these new artists writing all these new sounds, new music,” she says.

This was the early 1970s and Cambodia was in the middle of a music renaissance. Artists like Yol Aularong — a singer whose cheeky lyrics and bad boy attitude stole Thida’s heart — were shaping the scene.

While most fathers at the time might have discouraged their young daughters from diving headfirst into Phnom Penh’s music landscape, Thida’s father was different.

“You know normally dad won’t let the young girl go out and sing and doing all these things, my dad said, ‘You go play, you go do what you want. Art is beautiful,” Thida says. “It was a beautiful childhood I had here in Phnom Penh until the war.”

But in the background of Thida’s childhood, bombing campaigns by the United States as part of the Vietnam war and political upheaval meant Cambodia was growing more and more unstable. And in the countryside, a radical Marxist insurgent group — the Khmer Rouge — was steadily amassing power.

On April 17, 1975 the Khmer Rouge invaded Phnom Penh. The first thing the new regime did was tell everyone living there they had to leave. Thida was just 15.

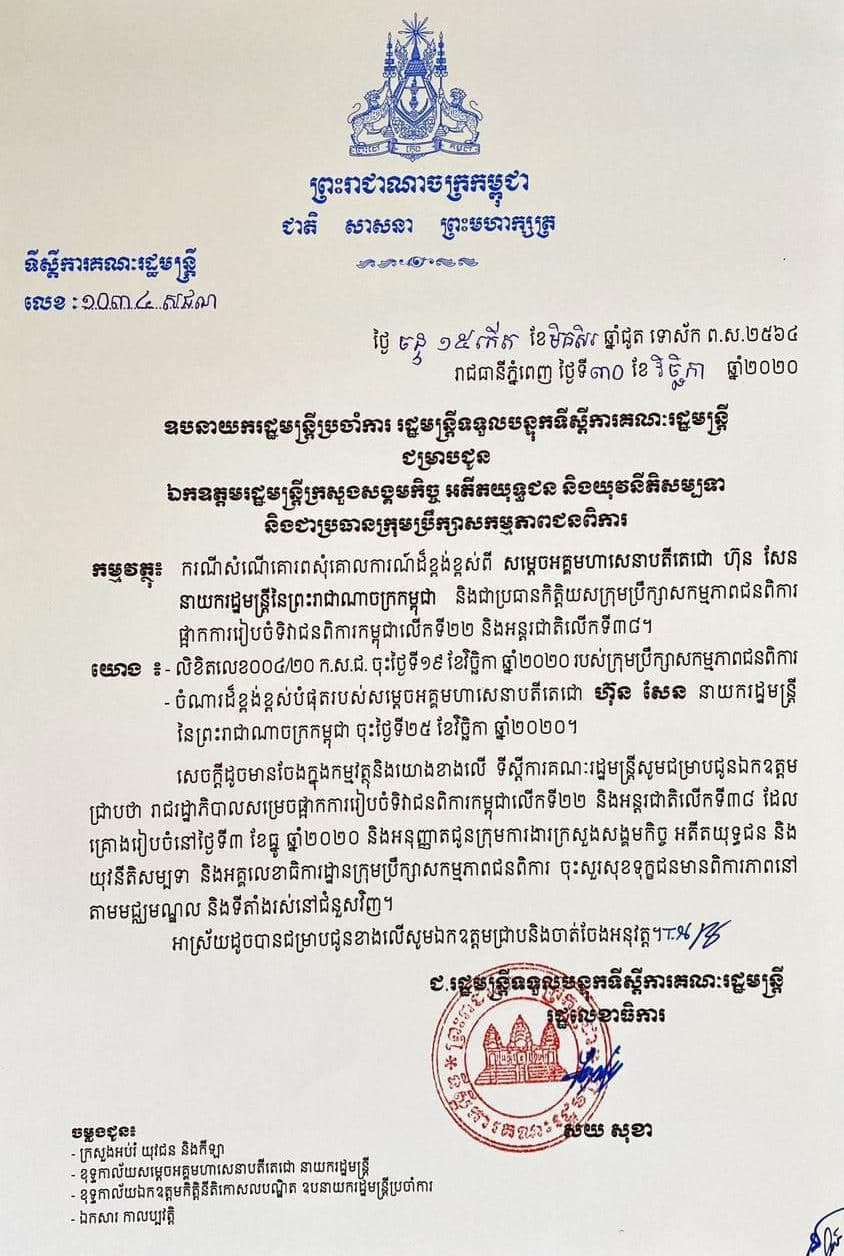

Courtesy of the Mam family

“We walked out of the city. Here we are: end of war, guns everywhere, tanks everywhere, my father tried to prevent me from seeing some of the dead bodies. There were floods of people on the street, we were sleeping on the street, there were women giving birth on the street — that’s how crazy the Khmer Rouge was,” Thida remembers.

At the time, the Khmer Rouge told the residents of Phnom Penh the evacuation would last only three days. The ordeal lasted more than three years.

The Khmer Rouge wanted to turn Cambodia into an agrarian utopia. To do that, they thought everything modern, international and intellectual would have to be destroyed. Educated, urban families like Thida’s were considered politically suspect and were forced to live under intense scrutiny in regime-controlled villages.

“As a child, I was wild,” Thida says. “And then [during] the Khmer Rouge, I had to shut down the feeling. It’s as if there’s a lid put on top of something that bubble[s].”

Thida’s three sisters and her mother survived those brutal years, but her beloved father did not. He was one of more than 1.5 million Cambodians who lost their lives.

When the Vietnamese army swept through Cambodia in 1979, Thida’s family fled across the border to a camp in Thailand. And in 1980, when Thida was 19, she and her family came to California as refugees.

Thida wanted her children to grow up feeling fully American — Laura and her younger brother had American friends and spoke English at home — but at the same time, Thida found ways to weave bits of Cambodia into their lives. Much of that revolved around music.

Thida sang Laura to sleep with Khmer lullabies, enrolled Laura in Cambodian dance lessons and played traditional Khmer folk music at home, but neither Thida, nor Laura felt much of a connection with the music that was coming out of Cambodia at the time.

The Khmer Rouge had targeted and killed musicians, including Yol Aularong, the cheeky singer Thida had loved. The Cambodian music industry that came after had been shaped by that grim reality. The result was a country whose airwaves were flooded with cheaply produced, karaoke-style covers.

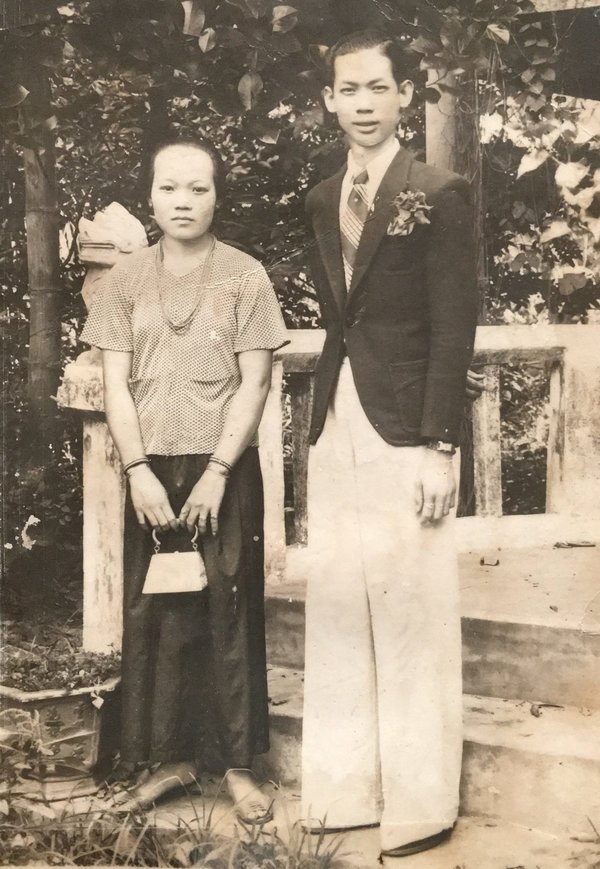

Andrew Mam/Courtesy of the Mam family

“There was no pride in that kind of music for me,” says Laura. Thida agrees.

“For the longest time, I listened to Thai music because it’s the closest thing to home,” Thida says. “But we were longing for something of our own. It’s a quiet longing.”

The global reaction to the song they wrote showed Laura and Thida they weren’t the only Cambodians who felt that way. So they wrote more.

Thida says the first thing she does when she and Laura are writing something new is to have Laura play the tune for her on guitar. “I just close my eyes and listen and feel her song.”

But the process wasn’t always easy. For Thida, helping Laura transform her lyrics from English to Khmer often meant not just translating words, but translating culture as well.

“Because language is about experience,” explains Thida.

“I would write these very American songs with such American attitude and then my mom would have to translate it into this really good girl who doesn’t break any of the rules and just loves with all the poetry of her heart,” Laura says.

But they got better at melding their points of view, and Laura’s fame in Cambodia started to grow. But fame alone wasn’t the goal: For both women, the real mission was to foster a more creative Cambodian music industry. To do that, Laura saw she’d have to leave California behind.

“Cambodia at that time was still this wild place to me, I’d been a couple of times, but never more than two months. But I knew that when I got off the plane, I felt something come alive in me,” Laura says.

Moving to Cambodia opened Laura’s eyes to what was happening behind the scenes of the country’s music industry.

“Once I got here, it was realizing that it’s not that people can’t do original music, it’s that they aren’t allowed to in the current system,” she says. “Karaoke houses were like ‘No, you can’t do original music because that would be only one album a year and I need to sell 12 to 25.’ Within one year, who could do that? Impossible.”

This was early 2015, and Laura and new original artists like her were finding ways around the industry’s barriers. These artists used Facebook and Youtube to circumvent the karaoke production houses and bring the songs they were writing straight to fans.

“It gave us a medium, outside of the controlled mediums that were existing at the time, to just do music as we saw fit. And then it just really broke the system,” Laura says.

Ten years ago, Lomorpich Rithy, who goes by the nickname Yoki, was one of Laura’s early fans. She remembers saving her money for a whole week just to pay for enough bandwidth to listen to Laura and Thida’s first song. Now, Yoki is one of the Original Music Movement’s staunchest advocates.

“I’m a filmmaker, a festival director and also [an] artist manager” Yoki says. She manages Small World, Small Band, another popular original music group.

To Yoki, Laura was, and still is, an inspiration. But, she says, this movement is more meaningful than just a handful of artists writing songs.

“We want to use the music as the new narrative for the world to remember Cambodia in a different way. We have been judged by our past like ‘Oh, you are the country of war.’ That was us before, but it’s not us now,” Yoki says.

Laura agrees.

“A lot of the time, if you read the comments there’s a lot of stuff on there that says ‘For the nation,’ and without the context you’d be like ‘What do you mean, for the nation?’ People see original music as this living proof that we are moving forward. It’s not the old Cambodia anymore.” Laura says.

In 2016, Laura and Thida created Baramey, their own production company dedicated to boosting original talent. The first group they signed was Khmeng Khmer, which means Khmer youth. It’s a pop/rap duo that’s now one of Cambodia’s most popular original acts.

“Once I saw the power that a local Khmer voice had I was like, this is the right thing. We’ve got to push this,” Laura says.

Five albums and 10 years after their first song together, Laura and Thida’s writing has helped Thida reclaim something the Khmer Rouge stole.

“Doing this is like being young again, because I never had the chance to be a teenager,” she says. “This is what I would have wanted to be, you know like, be silly, be brave.”

And it’s given Laura the chance to really see her mom.

“Her poetry is what made me see her as a human, not my mother. Suddenly I could see the woman who longed for love and longed for all of it,” Laura says. “It’s her ‘yes’ that gave me the ‘yes’ to go do this, and it’s still her ‘yes’ that I’m using to tell these artists ‘yes you can.’ ”

All those years ago, when Thida’s father gave her permission to be herself, he couldn’t have predicted his decision would have a ripple effect through war, across generations and continents to shape his nation’s music. But that’s exactly what’s happened. https://www.npr.org/