A daughter’s 40-year search for the truth behind the Khmer Rouge’s most haunting photograph

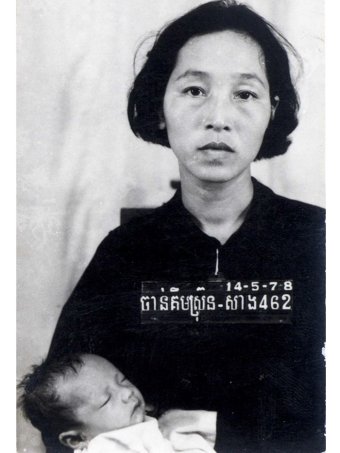

It is one of the Khmer Rouge’s most striking and haunting photographs.

Chan Kim Srun stares straight into the camera lens, holding her infant son in the Madonna and Child-like picture, rendered in black and white.

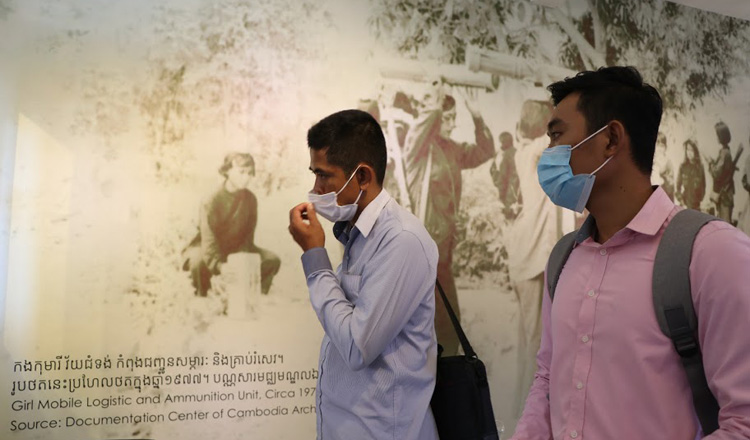

The powerful image has become a centrepiece at Phnom Penh’s genocide museum, serving as a reminder of the horrors committed by the Khmer Rouge

WARNING: This article contains content that some readers may find disturbing.

But Kim Srun also had two daughters. One of them, Sek Say, was 11 years old when this photo was taken.

She has spent the last 40 years trying to figure out the truth about what happened to her parents, who disappeared during the brutal communist regime.

Now, she thinks she knows the full story.

‘I was picking mangoes’

“I remember it was in late afternoon, I was picking mangoes,” Sek Say told the ABC, recalling the day when her parents were taken away.

The year was 1978. Three years earlier, the Khmer Rouge revolution had uprooted the lives of Cambodians, driving the population into the fields in the hopes of building a classless, agrarian utopia.

As a child, Ms Say was put to work cleaning medicine bottles at a hospital along with her sister Chreb, then aged nine.

“They took me from the hospital telling me I will be reunited with my parents. I was so happy,” she said.

“But when we drove past our home, I was curious why they did not stop,” she said.

She never saw her parents or her baby brother again.

“They took me to a new place — it is the place [for children whose] parents were executed. I lived there until the Khmer Rouge finished.”

‘I saw a teardrop close to her cheek’

In January 1979, a Vietnamese-backed force entered Cambodia, driving the Khmer Rouge into the north-west corner of the country.

When the military entered the capital, they discovered a devastating scene — in the heart of the city, the Khmer Rouge had transformed a school into a notorious prison, called S-21.

Up to 12,000 people were tortured there and sent to their deaths at the killing fields. Only a handful walked out alive.

Now named the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, the former prison houses thousands of haunting black-and-white portraits.

They capture the final moments of prisoners, who were often forced to pen “confessions” before they were killed, as the movement became increasingly paranoid and conducted frequent purges.

Among the walls of photos are the faces of Ms. Say’s parents.

Her mother’s is one of the most compelling, as she cradles her five-month-old son in her arms.

“I did not really recognize my mum immediately … but I remember my younger baby brother’s face,” Ms Say said.

“I began sobbing. When I looked closer at my mother’s photo, I saw a teardrop close to her cheek.

“I don’t know how my mother was killed or how they tortured her. I wondered how she would be feeling if she was thinking a lot of her children.

“It makes me think about what did they did to her during the interrogation if they pulled her fingernails out,” she said, before trailing off in tears.

Babies ‘smashed against trees’

The precise circumstances of her death are unknown, but Youk Chhang, head of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia (DC-Cam), said Kim Srun would likely have been taken to Cheoung Ek, the killings fields outside Phnom Penh.

There, prisoners were blindfolded, slit across the throat with sharp bamboo or struck on the back of the head, before being piled into mass graves.

At the site stands a tree with a chilling sign, indicating that infants were smashed against the tree.

Mr Chhang said testimony from S-21 guards casts doubt on that method of murder — some guards said babies were killed on the prison premises, to stop them crying — but there’s little doubt that the baby boy in the photograph was slaughtered.

The Khmer Rouge killed whole families, including children, abiding by the mantra:

“When you dig up the grass, you must remove even the roots.”

Mr Chhang said it was a visit to Cambodia from then US secretary of state Hillary Clinton in 2010, who paused at the photograph in the museum, that prompted the search for Ms Kim Srun’s family.

The photo was placed in a magazine and distributed across Cambodia: Kim Srun’s cousin recognised her, and told her only surviving child, Ms Say. Her sister Chreb had died of an illness shortly after the fall of the Khmer Rouge.

Ms Say broke down the first time she saw the photo, according to an account recorded in academic Alex Hinton’s book Man or Monster, about the trial of S-21 prison chief Kaing Guek Eav, better known as Comrade Duch.

“I can only recall that I was separated from my mother, I cried and went around searching for her. However, I could not find her,” Ms Say said.

Finding her father

Ms Say only learned of her mother’s fate in 2010, more than 30 years after the Khmer Rouge regime fell.

It would be another decade before she learned the truth about her father.

During a visit from members of the Holocaust Museum last year, Ms Say met with three former S-21 prison guards.

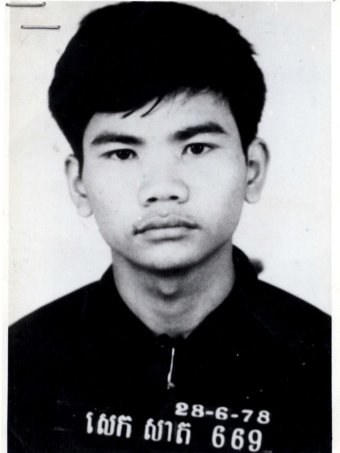

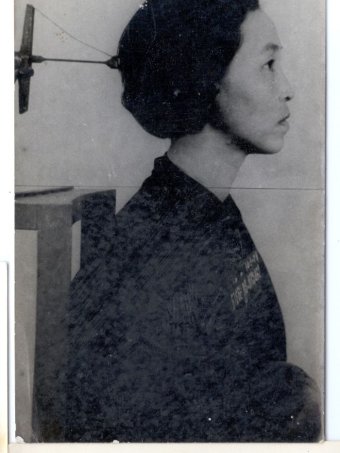

Last month, Sek Say was presented with the portrait of her father, Sek Sat, pictured in 1978.

“She was the purest, most honest survivor that I have ever met,” Mr Chhang said.

But the meeting made Mr Chhang realise he had become so absorbed by connecting Ms Say with her mother’s story, that they had never questioned what happened to her father.

Previous reports, like one published in the Wall Street Journal in 1997, incorrectly identified Kim Srun’s husband as the Khmer Rouge’s deputy foreign minister, Puk Suvann.

That story claimed both were overseas intellectuals who were “invited” back from exile in 1975 by Ieng Sary, the regime’s foreign minister at the time, who was later put on trial for crimes against humanity — however, he died before the proceedings could be completed.

Ms Say told researchers she only knew her father’s nickname — Prak — which is a common name in Cambodia.

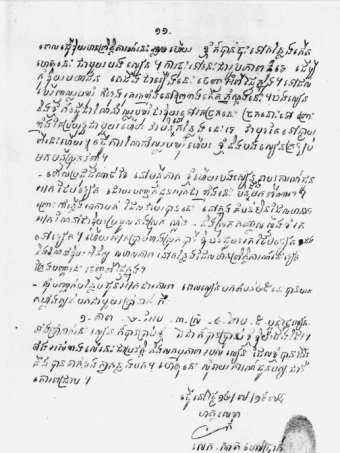

Documentarians then searched through their archives for men with the alias Prak, and just last month, they found his photo along with reams of paper — his “confession”.

His real name was Sek Sat.

Mr Chhang said the evidence was clear: the names of his wife and children were listed in the confession.

“We learned her father actually joined the Khmer Rouge for a long, long time, and he was also involved in an internal purge of Khmer Rouge cadres,” Mr Chhang said.

“He was one of the people who joined the Khmer Rouge because of social injustice that took place in the 60s and 70s.”

He was arrested in May 1978, along with his wife and baby son, and was accused of “creating activities to betray Khmer Rouge’s organisation”.

Prior to his arrest, he had risen through the military ranks to become a secretary in the country’s south-west, under the leadership of Ta Mok — one of the most senior deputies to Pol Pot, who was labelled “The Butcher” in the Western press.

Ms Say said it was a shock to learn of her father’s death — in the past, she had hoped he might still be alive.

“I don’t know what their roles were during that time because I was a kid, I only know he was a soldier,” Ms Say said.

“I feel very unfortunate that they were working [for the Khmer Rouge] but still got killed, and I found it extremely hard to live without parents.”

Unearthing a dark past

For anthropologist and genocide expert Alex Hinton, the discovery speaks to an uncomfortable truth about those killed at S-21 — many victims were in fact Khmer Rouge cadres themselves.

He said there were often murky ethical questions attached to mass atrocities.

“The photograph of the mother and the child, it’s an image of pure victimhood … But the truth is, the situation is often much more complicated,” he said.

“The people are passing through S-21 at a time [when] huge numbers of them were former soldiers. Some of them had a lot of blood on their hands.

“But at the same time … the key insight is that they ultimately became victims, and they suffered as well.”

The Khmer Rouge sought to sever family links in order to cement loyalty to the regime.

“Children were asked to report on their parents,” Professor Hinton said.

“They were being brainwashed at the time because the state wanted the loyalty to be to the organisation, to the revolution.”

He pointed out the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum — named 40 years before the crime of genocide was actually proven against the Khmer Rouge’s senior leaders — also had a political element to its construction.

The Vietnamese-backed government was preserving and showcasing evidence of the Khmer Rouge’s crimes, in part to legitimise their invasion of the country. The Khmer Rouge still had a seat at the United Nations up until 1993.

Professor Hinton said the prominence of the photograph was partly designed to devastate the observer.

“The iconic image of a mother and a child, especially a baby, [conveys] the notion of complete innocence,” he said.

“When you stand by it, you see yourself reflected in the glass and the light.

“And so it also may be somewhat disconcerting.”

Finding answers to questions about what happened to family members was part of a broader “right to truth”, he said, and particularly important in Cambodia: reincarnation is a central belief of Buddhism, and those who die a violent death are often not reborn.

“Everybody wants to know what happened to their loved ones,” he said.

For Ms Say, seeing the photo of both her parents at last was important closure, but still a source of deep and enduring pain.

“When I first saw the photo, I found it extremely difficult,” she said.

“It was very sad to see her photo, knowing she was immediately killed.”

ABC News