Good Practice on “Factory Literacy Program in Cambodia”

Cambodia has one of the fastest rates of urbanization in Asia: in the last decades, Phnom Penh’s population has doubled and the urban population is now 21 percent (Hut, 2016). Many of these rural-urban migrants are women migrating to work in factories; many have low literacy levels. Lessons learned from Cambodia’s 2015 National Literacy Campaign of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport (MoEYS) suggest that most of the young literacy learners in the Community Literacy Program aged between 15-24 years had moved to urban areas to benefit from employment and better economic opportunities in garment and manufacturing industries. The 2013 report by the Ministry of Planning on Women and Migration in Cambodia showed that 85 percent of the 605,000 workers in garment and footwear factories were women, of whom 14 percent were illiterate and 29 percent demonstrated low levels of literacy.

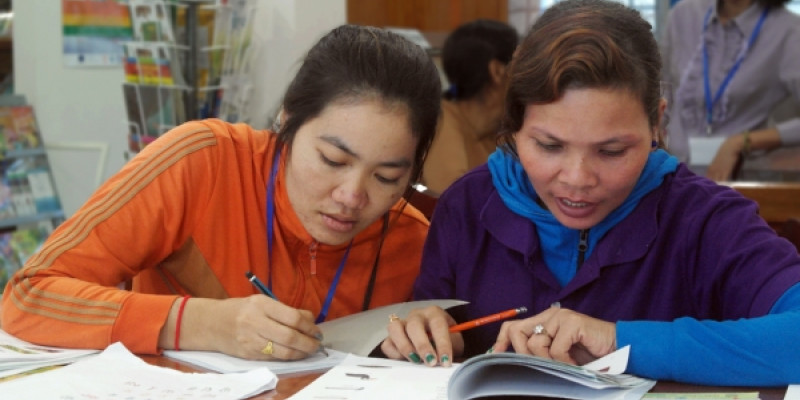

The Factory Literacy Programme (FLP) was initiated with support from UNESCO’s Capacity Development for Education Programme (CapED) Programme, formerly known as Capacity Development for Education for All (CapEFA) and subsequently funded through the UNESCO Malala Fund for Girls’ Right to Education. The FLP aims to enable young women and girls working in factories aged between 15 to 45 years to acquire basic functional literacy skills and empower them to better understand their own fundamental rights. At the same time, this program supports the government and factories to engage in Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Cambodia.

With the implementation of the FLP for over two years from 2016 until December 2019, the following achievements have been made and recognized by MoEYS. The program has prepared 47 teachers (25 female), 1,300 learners (95% female) have completed the program, and 12 MoEYS (2 female) and 12 PoEYS officials (3 female) and 25 (8 female) managers in 25 factories received an orientation (in Phnom Penh, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Kampong Chhnang, Kampong Cham, Thbong Khmom, Prey Veng, Svay Rieng, and Siem Reap provinces). Recognizing these results, MoEYS has further encouraged other factories to implement the classes and has offered to allocate 24 contract teachers. As part of the initiative, MoEYS has currently provided 19 contract teachers already, a number that will grow as more factories implement literacy classes in the future. In addition, as part of the project, there was strong cooperation and coordination between the government, factories, NGOs and UNESCO.

Each partner had specific roles related to their areas of expertise. UNESCO funded the program, provided upskilling training for teachers, printed textbooks and materials for learners, and supported the establishment of Reading Corners in 9 factories. Sipar provided support for designing the learner textbooks and continued to provide technical support and monitoring of literacy classes and libraries; ILO trained literacy teachers to deliver Rights at Work and Decent work for Youths instruction, and Garment Manufacturer Association of Cambodia (GMAC) provided the network to inform and encourage factories to join the program. Cambodia Women for Peace and Development (CWPD) provided input on life skills topics, support to teachers, helped with library and Reading Corner management and used its network to encourage factories to join. MoEYS financed textbook developers, recognition of the program, teacher training and teacher salaries, and the District Office of Education (DOE) and Provincial Office of Education, Youth and Sport (POEYS) provided initial support for setting up the classes and ongoing observation and support.

The Factory Literacy Program (FLP) conducts classes during working hours when workers are available to learn, has a shortened learning time (3- months) and uses interactive teaching methods. The current factory program is shorter, more accessible and the curriculum is more targeted to learners’ needs. The learners are also factory workers, who see the benefits of literacy directly applied to their current jobs. This is very different from teaching farmers who do not have time or are tired or factory workers on the weekend when they come home and are tired too. According to its final evaluation report (PRI, April 2019), the learners, teachers, and factory managers all see obvious progress in improved literacy, maths, confidence, knowledge and behaviors. The learners’ families are also positively impacted, with women reporting that their husbands saying they are ‘braver’ to talk to others and to try new things, and children seeing their mothers learning how to read. Workers feel more confident and report that they treat others better, which factory managers noticed as well. Learning to read is a profound experience that changes how a person sees themselves, with one learner putting it best: “now I am like a new person…. before, I had to ask for help. I felt like a blind person… now I feel happy and less stressed.” The ability to read allows them dignity, pride, and more autonomy in their own lives. In addition to learners’ personal lives, their work lives have improved as well, with many reporting that they receive more responsibilities and are more respected. Managers report that learners are performing better at their jobs and are able to work faster, as they do not need to ask others’ help with reading.

The Factory Literacy Program (FLP) is flexible in that classes can occur at any time of day, for any length of time, depending on the factory manager’s decision. Most factories have the literacy program at lunchtime for workers, as this does not impact production, does not cause the workers to lose time at work or cause others to have to make up time lost. Workers frequently ride trucks to work and the trucks leave on a schedule to bring them home, so learning before or after work is not possible. As one Garment Manufacturer Association of Cambodia (GMAC) official pointed out, “factories lack the space for classrooms and they lack the time for learning: it’s a factory, not a school. We have to try to convince the factories of the usefulness of this project so they make the decision to join.” The program needs to be flexible and responsive to both factory production needs and worker needs. The program offers literacy and numeracy skills along with life skills. The life skills topics were selected after interviewing potential participants about what they would like to learn and what is important in their lives. This approach, of responding to the needs of learners, is consistent with mainstreaming gender approaches endorsed by UNESCO. In addition, the program encourages the development of soft skills (such as teamwork, listening skills, and communication skills) through interactive teaching methods, group work, pair work, and presentations.

These soft skills are very important in helping migrant women integrate into their new communities; as The Cambodian Rural-Urban Migration Project (CRUMP: 2012) research showed, nearly 40 percent of women migrants recently felt lonely. It is difficult to make friends when moving to a new place and the program provides opportunities to get to know people while attending a class together.